in Story & News

The Definitive “Joseon Artwork” Debate:

An Exploration In Self-identity

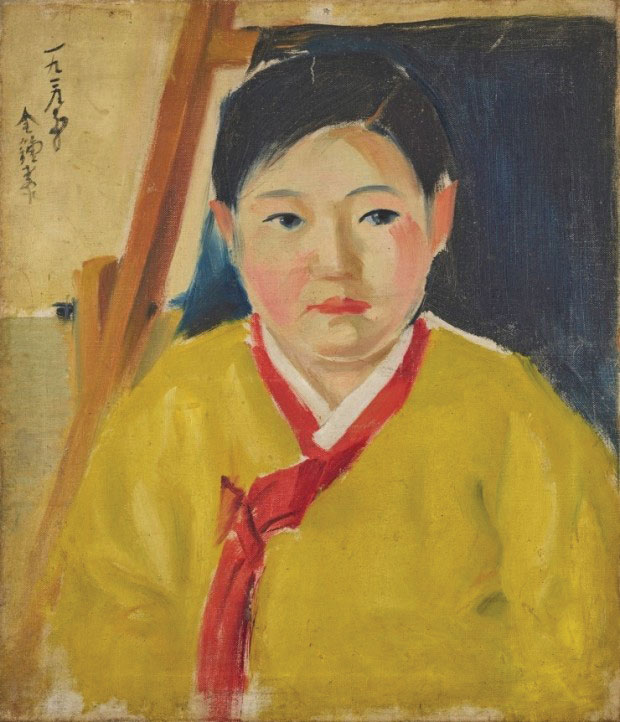

Jung-hyun Kim’s Springtime and Chong-tai Kim’s Yellow Top

In 2017, Jung-hyun Kim’s Springtime (1936), previously known only through photographs, was finally unveiled to the public. The National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art acquired the piece from a private collector, restored it over four months, and revealed it to the world. This grand artwork, painted in the traditional Korean style on a fourpanel folding screen, stands as an imposing masterpiece with its massive scale (106×54.2×(4) cm). Its debut captivated audiences with its overwhelming charm. Even at the time of its creation in 1936, Springtime attracted widespread attention, earning an unprecedented distinction by winning awards in both the Eastern and Western painting categories of the Joseon Art Exhibition.

By Prof. Jung-hwa Kang, Department of Korean Language Education, Korea University

Jung-hyun Kim, Springtime, color on paper, 1936.

collection of the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea.

The Joseon Art Exhibition and Korean Identity

The Joseon Art Exhibition was an annual art competition organized by the Japanese colonial government from 1922 to 1944. Winning entries were showcased through the exhibition, which became one of the most significant cultural events in colonial Korea, a period when newspapers and magazines were the primary entertainment media. Crowds from across the country flocked to the exhibition in Gyeongseong (modernday Seoul), and award winners quickly rose to prominence in the art world. The exhibition held special significance as a gateway for aspiring artists, particularly those without access to overseas education or formal art training. It played an essential role in nurturing artists during this era.

However, the Joseon Art Exhibition had a critical flaw: its jury consisted exclusively of Japanese officials. This meant that the art favored by the organizers often depicted Korea not as a modernizing nation but as a romanticized vision of its premodern past. Westerntrained Korean artists often refused to participate, forming independent groups to pursue their creative visions. Critics also lambasted the exhibition for promoting what they saw as an “exoticized Korea.” One prominent critic, Heesoon Yoon, criticized the repetitive depictions of traditional Korean motifs such as “yellow tops, thatched roofs, crumbling mud walls, women carrying water jars, and children strapped to their mothers’ backs.” This sparked debates about “local color” and its role in Korean art.

While some dismissed the traditional themes showcased at the exhibition as pandering to colonial stereotypes, others saw value in exploring them. Artists and critics debated what “local color” truly meant and grappled with the broader question of Korean art identity. This “local color debate” wasn’t merely about aesthetics; it was a journey to uncover the essence of Korean art. It led to profound reflections on what defined the spirit of Korean creativity. Today, this debate resonates with a question relevant to our time: What was the art of Korea, and what can it teach us about our artistic identity now?

Jung-hyun Kim: At the Heart of the “Local Color Debate”

Jung-hyun Kim, who painted scenes rooted in the essence of Korean life during the days of the Joseon Art Exhibition, was inevitably swept into the broader “local color debate.” For him, however, participating in the exhibition was less a matter of artistic choice and more a necessity. Balancing his art with jobs as a tram conductor and store clerk to make ends meet, the Joseon Art Exhibition provided Jung-hyun Kim his sole avenue to pursue life as a painter.

Springtime, as its warm title suggests, portrays a tranquil domestic scene: five women preparing food or caring for children alongside three children at play. The diverse colors of the women’s traditional upper garments bring vibrancy to their movements, creating a sense of dynamic life. Despite the variety of narratives within the painting, the overall mood feels cohesive and warm, thanks to the harmonious use of yellows, oranges, earthy tones, and teal hues. This warmth reflects everyday scenes familiar to viewers of the time. The renowned art critic and painter Seok-ju Ahn praised Jung-hyun Kim’s ability to capture what he called “a purely unvarnished sense of local color.”

However, another critic, Hee-soon Yoon, harshly criticized Jung-hyun Kim’s work, calling it “a failed piece corrupted by the ideology of ‘local color.’” Yoon’s critique centered on his belief that Jung-hyun Kim’s works were deliberately crafted to align with the colonial government’s aesthetic agenda. While he acknowledged the technical skill in Jung-hyun Kim’s paintings, Yoon dismissed them as “fabricated and falsified works” driven by ulterior motives.

Yoon’s perspective was not entirely unfounded, as artists participating in the Joseon Art Exhibition were undeniably influenced by the preferences of its Japanese jury. Yet to label works featuring Korean traditions as inherently inferior diminishes their artistic significance. Jung-hyun Kim’s 1941 painting Shaman’s Portrait is a prime example. This piece, which centers on a shaman and vividly depicts Korea’s fading shamanistic traditions, is often celebrated as one of the most quintessentially Korean artworks. The bold, vibrant colors contrast with the hazy background, evoking the mystique of Korea’s spiritual heritage. To dismiss such a work as a mere pandering to judges’ tastes oversimplifies its intent and meaning. Instead, Shaman’s Portrait reflects Jung-hyun Kim’s deep engagement with the question, “What is Korean art?” Writer and painter Yong-jun Kim once described Jung-hyun Kim’s and Chong-tai Kim’s works as those that “most prominently attempt to convey the unique essence of Korea.” This acknowledgment underscores that Jung-hyun Kim’s legacy is not merely about conforming to expectations but about grappling with the core identity of Korean art. His commitment to tradition and his exploration of “local color” stand as testaments to the complexities of defining a nation’s artistic identity under challenging circumstances.

“Rather than depicting novel subjects in extraordinary ways, I wish to portray the everyday things we constantly see and hear, revealing the local color imbued in them.”

- Chong-tai Kim

Chong-tai Kim, Yellow Top, oil on canvas, 1929.

collection of the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea.

Jung-hyun Kim, Shaman’s Portrait, oil on silk over plywood, 1941.

collection of the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea.

Chong-tai Kim: The Painter of Everyday Splendor

Another artist who sought to express the essence of Joseon through its traditions, much like Jung-hyun Kim, was Chong-tai Kim. Frequently mentioned alongside Jung-hyun Kim by Yong-jun Kim, Chong-tai Kim is remembered as a painter who captured the everyday life of Joseon on canvas. Though his name is less recognized compared to figures like Whan-ki Kim, Soo-keun Park, or Jung-seob Lee, Chong-tai Kim left an indelible mark on the 1920-30s art scene. Making his debut by winning a prize at the Joseon Art Exhibition in 1926, Kim went on to receive consecutive top honors from 1927 onward, becoming a prominent figure in the art world. A graduate of a teacher’s college and an elementary school teacher by trade, he lacked formal art education. Ironically, this absence of formal training became a strength, enabling him to carve out a unique identity in the academicdominated art scene. Chong-tai Kim’s lively brushstrokes and bold compositions stood apart from conventional styles, earning him recognition and acclaim.

The artist’s distinctiveness is evident in works such as Yellow Top and Nap Time. Both pieces showcase light, energetic brushwork and daring color choices. The composition itself deviates from convention, as the subjects are captured at a slant, creating a dynamic perspective. It was this innovative approach that led the painter Byung-don Song to describe Chong-tai Kim as “a painter of unique brilliance.”

Despite his modern techniques and fresh approach to subjects, Chong-tai Kim’s focus remained on tradition. His works demonstrate that portraying tradition need not feel antiquated. The reason Chong-tai Kim sought to capture traditional moments even while experimenting with new methods was his belief that local color resided in the everyday. He once mentioned that Korea’s traditions could be found in familiar items, such as the embroidered pines, cranes, lingzhi mushrooms, and clouds adorning the folding screens or utensil holders of his childhood.

A girl in a yellow top, fading customs, or works submitted to the Joseon Art Exhibition—these cannot simply be dismissed as pandering to external tastes. The landscapes and figures these artists painted were not mere replications of Joseon; they were intense reflections on the identity of Korean art. It is through such reflections that the foundations of today’s art have been built. As such, these questions persist, prompting us in the present to ask anew: What makes our art definitively Korean Art?

Chong-tai Kim, Nap Time, oil on canvas, 1929.

unknown ownership.