News & Events

Press Releases

International Comparison of Women’s Employment Indicators and Their Implications

|

61.4% employment rate among Korean women;

Korea (rank 31) was in the lower tier among OECD member states for the past 20 years

• Korea ranks 31st among the 38 member states of the OECD for women’s (ages 15 to 64) employment rate1) (2023), recorded at 61.4%

* For the past 20 years (2003-2023) Korea ranked in the lower tier (rank 26 to 31) among OECD member states in terms of employment rate among Korean women

* The labor force participation rate among Korean women in 20232) was 63.1%, also ranking in the lower tier (rank 31) among OECD member states (average 66.7%)

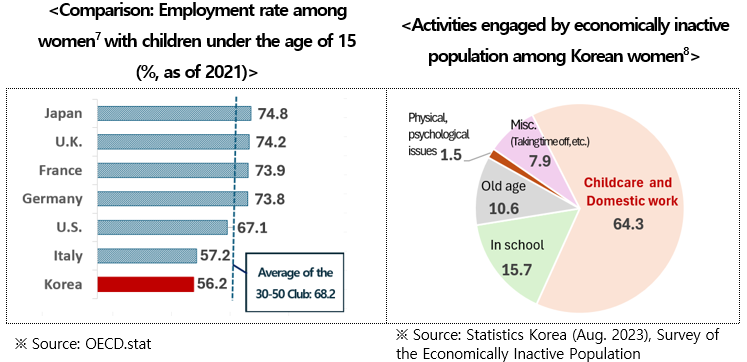

• The employment rate of women with children3) in 2021 for was 56.2% for Korea vs. an average of 68.2% among 30-50 club4) countries

* Among activities engaged by women among the economically inactive population in Korea, the ratio of those engaged in ‘Childcare and domestic work’ (64.2%) was the highest

• A women-friendly work environment needs to be cultivated, including by establishing a flexible work environment and expanding support for family care

1) Employed persons aged 15 to 64 / Total population of persons aged 15 to 64 (Working-age population) × 100

2) [Employed persons aged 15 to 64 + Unemployed persons aged 15 to 64] / Total population of persons aged 15 to 64 (Working-age population) × 100

3) Women with at least 1 child below the age of 15

4) The 30-50 club: Refers to countries with per capita GDP exceeding $30,000 and population more than 50 million—which includes the U.S., Japan, the U.K., Germany, Italy, France, and the Republic of Korea

It has been shown that for the past 20 years, Korean women’s employment indicators (employment rate, labor force participation rate) remain in the lower tier among OECD states. It has been put forth that to expand women’s workforce participation and raise employment levels, there is need for ‣Establishing flexible work environments and ‣Policy measures to ease the burden of family care.

61.4% employment rate among Korean women; Korea (rank 31) was in the lower tier among the 38 OECD member states for the past 20 years

Korean women’s labor force participation rate (63.1% as of 2023) was also in the lower tier (rank 31) among the 38 OECD member states

The Federation of Korean Industries (hereinafter, FKI, Chairman Jin Roy Ryu) conducted an analysis of women’s (between ages 15 to 64) employment indicators among the 38 OECD member states. The analysis showed that in 2023, the employment rate and labor force participation rate for Korean women was 61.4% and 63.1% respectively, and Korea was ranked among the lower tier (rank 31 for both indicators) among OECD member states.

The OECD ranking for the past 20 years (2003-2023) shows that Korea’s employment rate of women in 2003 was at rank 27 (51.2%), but slipped 4 ranks in 2023 (61.4%) to stand at rank 31. For the past 20 years, Korea has remained among the lower tier (between ranks 26-31). During the same period, Korean women’s labor force participation rate in 2003 (53.0%, rank 32) went up 1 rank in 2023 (63.1%). However, Korea has been ranked among the lower tier of the OECD for the past 20 years (2003-2023), remaining between ranks 31-35.

Employment rate of women with children under the age of 15:

Korea (56.2%) vs. (68.2%) average among 30-50 club countries

The employment rate of women with young children was lower in Korea than in key countries with comparable economic and population size. As of 20215), the employment rate of women with children under the age of 15 in Korea was 56.2%, the lowest figure among the 7 countries among the 30-50 club. Compared to the average (68.2%) among 30-50 club countries6), Korea’s figures stand 12.0%p lower, which is a significant gap compared to advanced economies.

5) As of 2021, according to latest available OECD data

6) Calculation method: Arithmetic mean of the 7 countries’ employment rate statistics among the 30-50 club

The FKI remarked, “The burden of childcare and domestic work in Korea are the main reasons that inhibit women’s workforce participation.” The FKI further noted, “To expand the level of employment of women to those of advanced economies, policies must be focused and advanced to lower the burden of balancing work and family for women.”

7) Women between the ages 15-64 with at least 1 child below age 15

8) Persons neither employed nor unemployed and not looking for work

Enhancing the employment rate of women, it is necessary to ➊Establish flexible work environments and ➋Expand family care support

The FKI compared the work environment of 3 countries among the 7 countries of the 30-50 club9) with employment rates of women that exceed 70%--Germany, Japan, and the U.K.—to that of Korea with the aim to identify the characteristics of advanced countries with high employment rates of women. The FKI finds that compared to the previous 3 countries, Korea needs to make improvements in two areas: ‣Establishing flexible work environments and ‣Expanding support for family care.

9) Employment rates among women in the 30-50 club countries (As of 2023): ‣Germany 73.7%, ‣Japan 73.3%, ‣U.K. 72.2%, ‣U.S. 67.5%, ‣France 66.0%, ‣South Korea 61.4%, ‣Italy 52.5%

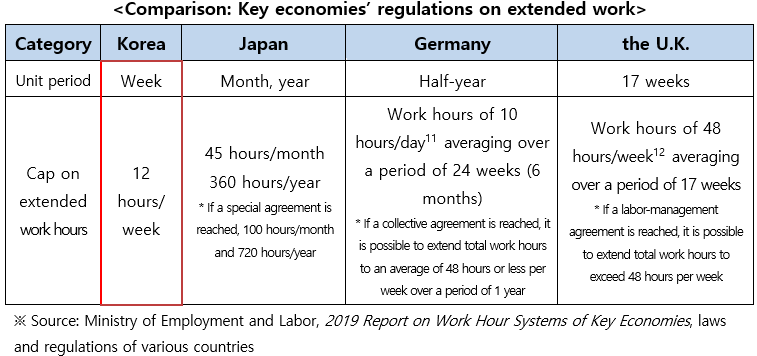

[➊Flexible work environment] There is a wider range of options in Germany, Japan, and the U.K. for work hours than in Korea, affording workers a flexible work environment that enables balance between work and childcare.

In terms of work hour options, work hour limitations in Korea are prescribed on a weekly system and are limited to a maximum of 12 hours per week. However, the German, Japanese, and English systems are based on a monthly or longer unit period, allowing more flexibility in work hours.

In terms of the flexible work hour systems10), Korea’s system is based on a 6-month maximum unit period. However, the German, Japanese, and English systems are based on a maximum 1-year unit period, allowing a wider range of options for work hours.

10) Flexible work hours system: A work hour system that may be adjusted according to workload, provided that a labor-management agreement is reached

11) Refers to “Total work hours,” the sum of statutory work hours and extended work hours

12) Ibid.

[➋Support for child and family care] It has been shown that Korea’s child support and family care policies were less comprehensive than in Germany, Japan, and the U.K.

Korea’s family policy expenditures accounted for 1.5% of GDP13) as of 202014), which was lower than the average (2.2%) of ‣Germany (2.4%), ‣U.K.(2.3%), and ‣Japan (2.0%). In particular, cash expenditures for family policies accounted for only 0.5% of GDP in Korea, which was only half as high as the average (1.0%) of ‣Germany (1.0%), ‣U.K. (1.3%), and ‣Japan (0.8%).

13) Family policy expenditures: Expenditures that support child and family care, etc. May be categorized into two branches—cash benefits and in-kind benefits. Cash benefits include family allowance and childcare leave allowance; in-kind benefits include education and caregiving for young children and infants as well as family caregiving services.

14) As of 2020, according to latest available OECD data (German data as of 2019)

(Japan) Key caregiving policies in Japan include the 2013 Accelerated Plan for Reducing Wait-listed Children15) which expands childcare facilities and services. This policy aims to assist women who suspend their employment due to difficulties finding childcare facilities. The policy impact was significant, leading to the total number of childcare and daycare facilities rising from around 29,000 in 2015 to around 40,000 in 2023—and the number of children in waitlists decreased from around 23,000 in 2015 to around 3,000 in 2023.

15) “Wait-listed children” is a term in reference to the shortage of care facilities for children in Japan. Although children have been signed up to enter a facility, many had been put on a waiting list and had to stand by to be granted access to a care facility.

(U.K.) The U.K. government helps alleviate high childcare costs and encourages workforce participation by providing workers who work 16 or more hours per week and have children under the age of 11 with up to £2,000 annually. Children who are 3 or 4 years old of workers with less than a certain income are eligible, annually, for 570 hours of education free of charge.

(Germany) The Federal Financial Assistance Law for Daycare Expansion, enacted in 2007, stipulates the statutory rights of access to daycare facilities for children aged 1 year or older. If childcare services are unavailable due to lack of childcare facilities, the local government must provide parents with appropriate compensation.

“In Korea, the burden of child and family care are disproportionately borne by women,” FKI notes, “In order to establish an environment conducive to more active workforce participation of women, policies that help alleviate the burden of family care, such as securing more childcare facilities and services as well as expansion of support for caregiving costs, must be strengthened.”

Sang-ho Lee, head of FKI’s Economic and Industrial Research Department commented, “In order raise employment rates among Korean women to advanced economies’ levels, it is crucial to maintain and expand jobs held by women with children.” He emphasized, “We must actively promote women’s workforce participation by establishing a work environment that enables work-family balance, through such measures as providing a flexible work environment and expanding quality part-time jobs, and by bolstering family care support.”